…next year, I won’t be comparing seasons 1994 and 2024. Instead, I plan to post short biographies that I’ve written for my e-book “…from Phil Dent to Jannik Sinner…” (published in March 2021) focusing on the best singles players of the Open Era. I’ve included 340 short biographies in the e-book and intend to share over 100 on my website. These will be slightly modified versions, adjusted to suit my website and hyperlinked. This project will be titled

…next year, I won’t be comparing seasons 1994 and 2024. Instead, I plan to post short biographies that I’ve written for my e-book “…from Phil Dent to Jannik Sinner…” (published in March 2021) focusing on the best singles players of the Open Era. I’ve included 340 short biographies in the e-book and intend to share over 100 on my website. These will be slightly modified versions, adjusted to suit my website and hyperlinked. This project will be titled

“…from John McEnroe (b. 1959) to Kei Nishikori (b. 1989)”

aiming to showcase the best players of the past forty years, spanning the most successful individuals from the 1980s, 90s, 00s, and 10s. This year in December, I’ve already posted fifteen biographies. Next two years, I aim to post between 3 to 7 biographies each month. Whether it’ll be completed within those two years remains uncertain; it largely depends on potential retirements. Notably, ten very good/great players born in the 80s are still active as of the end of 2023. You can find the links to the biographies here. Additionally, I’ll continue to post picture-stats of the most significant matches from the Open Era. Furthermore, I’ll keep posting pic-stats of Federer’s finals. As of the end of 2023, there are 138 out of his 157 finals available on my website; I guess the remaining 19 finals will be posted by the end of 2025. This means 87% of his finals are wrapped up, it’s 84% in Đoković’s case, 83% in Nadal’s.

Rivalry at the Top

In 1993, the entire season was captivated by the rivalry between two US players: Pete Sampras and Jim Courier. One year older Courier continued his astounding form on clay and hardcourts, which had begun at Indian Wells ’91, while Sampras finally lived up to the expectations set by his US Open ’90 title. However, the latter part of the season saw an abrupt end to this rivalry. Courier lost his form, and concurrently, Michael Stich, who had been relatively successful earlier in the season, surged, dominating the autumn of ’93. Looking back, Stich may be regarded as the most successful player in the final quarter of the season, clinching three indoor titles, two of which were highly prestigious (especially Frankfurt), and leading Germany to victories over Sweden and Australia in the Davis Cup, triumphing over almost all the top-ranked players of that time.

Thirty years later, the first half of the season was marked by a rivalry among three players: Novak Đoković, Carlos Alcaraz, and Daniil Medvedev. Jannik Sinner joined in the latter part of the season, initially in a more cautious mode as his Wimbledon semifinal and victory in Toronto were partially due to very favorable draws. In the autumn, he ascended to a higher level, defeating all three higher-ranked players multiple times, including Medvedev thrice and Đoković twice.

The Fall

Guy Forget, one of the leading players of the early ’90s, suffered a severe injury at Hamburg ’93, sidelining him for nearly a year and causing a significant drop in rankings from no. 17 to 623. That year was critical for Ivan Lendl, the most dominant player of the ’80s, as it was the first time since his teenage years that he was unable to be competitive in the “best of five” format. He also lost his edge in crucial moments of tighter sets, a trend that continued in 1994, leading to his retirement at the age of 34. Andre Agassi, a Top 10 player from 1988 to 1992, experienced the first of his two major crises in his long career (the second would occur in 1997), resulting in a plummet to no. 24 by the end of the season.

Three decades later, more elite players had a disastrous season, especially Rafael Nadal, one of the greatest players of all time, who participated in only two events at the beginning of the year and dropped from no. 2 to 670 (two places below him is Marin Čilić, the former US Open champion, who also played just two events this year, beginning it as no. 17). Nadal’s compatriot Pablo Carreño Busta falls down from no. 13 to 606 having played three ATP events (two Challengers). Nine years younger than Nadal, Nick Kyrgios played just one event, resulting in his disappearance from the ATP ranking after being ranked no. 22. Matteo Berrettini, another significant name in the past few years, faced physical problems throughout the ’23 year, plummeting from no. 14 to 92. The 27-year-old Berrettini began and ended the year positively, first aiding Italy in reaching the final of the United Cup, and then concluding the year on the bench, motivating his younger Italian compatriots during the Davis Cup triumph.

The Rise

Nineteen-year-old Andrei Medvedev was a rising star in 1993. The Ukrainian, with a somewhat wooden yet efficient style, proved to be successful on all surfaces. Many pundits viewed him as a potential main rival for Pete Sampras in the second half of the ’90s. However, Medvedev’s peak was actually reached the following year, before he turned 20. Although four of Medvedev’s peers finished their careers with more accomplishments, in 1993, none of them was frequently mentioned in the same breath as Medvedev. Here’s a ranking comparison of the best players born in 1974 at the end of 1993:

6 – Andrei Medvedev

76 – Àlex Corretja

88 – Thomas Enqvist

102 – Yevgeny Kafelnikov

372 – Tim Henman (before his ATP debut)

Two prodigies born in 2003, Carlos Alcaraz and Holger Rune, confirmed their tremendous potential displayed a year before. As I write this, it seems they along with two years older Jannik Sinner – could create a new “Big 3” in the ’20s. However, it’s a shallow assumption that doesn’t account for super-talented players born in the mid-2000s who might emerge in a few years. The current best teenager, Arthur Fils, is ranked 36. My early estimation suggests he may have a more successful career than a fellow Frenchman, Gaël Monfils.

Veterans

The age of veterans shifted from the age of 30 to 35 over thirty years. In 1993, there were few players who could turn 30 and still pose a threat. One of them was Ivan Lendl, mentioned earlier, but at 33, he reached his physical limits. Other famous players in their thirties who were approaching the twilight of their careers included Brad Gilbert (32), Anders Järryd (32), as well as Mikael Pernfors and Henri Leconte, both at 30. The former French Open champion Andrés Gómez decided to retire at 33 in 1993 while four years older Björn Borg, the icon of the 70s, finally played the last match in his professional career, ultimately completing his retirement which had been initiated… ten years earlier. Thirty years later the most significant name to finish career is John Isner (38), a man who brought serving and playing tie-breaks to another level.

In 2023, Novak Đoković defied the age paradigm by securing three major titles and enjoying one of the best seasons of his illustrious career at the age of 36. Other players from his generation still achieved notable results: Andy Murray, only seven days older than Đoković, reached the final in Doha; 37-year-old Gaël Monfils triumphed in Stockholm; his contemporary Richard Gasquet commenced the season with a title in Auckland, and 38-year-old Stan Wawrinka was a runner-up in Umag. Feliciano López, aged 42, reached the quarterfinals in his farewell event this year (Mallorca). Thirty years ago the oldest player to win an ATP match was Jimmy Connors (41). Below is the ranking of players aged 35 and above in the Top 100:

1 – Novak Đoković

42 – Andy Murray

49 – Stan Wawrinka

74 – Gaël Monfils

76 – Richard Gasquet

Game-styles

In 1993, the trend initiated in the late ’80s/early ’90s continued, transitioning from aluminium racquets to graphite ones (Cédric Pioline was a significant exception), which led to increased serve-and-volleyers garnering points directly behind their serves, primarily focusing on tie-breaks. Notably, Pete Sampras, Michael Stich, Goran Ivanišević, and Richard Krajicek epitomized this style, contrasting with players like John McEnroe (finished his career at the end of 1992, but took part in two exhibition events of ’93), Stefan Edberg or Pat Cash (due to injury he missed the entire ’93 season), who were faithful to the chip-and-charge strategy as returners. Boris Becker stood somewhat in between; in the mid-’80s, he was a prototype for players who emerged in the early ’90s. Canadian Greg Rusedski entered the scene in 1993, known later for breaking his own records in serve-speed as well as being super dependent on tie-breaks. At that time, the magical velocity touched 200 kph (125 mph) – rarely crossed by servers. Other young player, who gathered some attention in 1993 it was Australian Patrick Rafter, a follower of the McEnroe/Edberg tradition. These two “R” native English speakers would face each other in an unexpected US Open ’97 final, and Rafter’s finesse triumphed over a show of brute force in a duel of two different S/V mindsets. Rusedski finished the year 1993 ranked 50th, Rafter 16 places below. More than four years later they’ll enter an event trying to become world’s no. 1 (Key Biscayne ’98).

At the end of 1993 in the Top 20, there were eight serve-and-volleyers, nine offensive baseliners, and three defensive baseliners (noting that Michael Chang was improving his serve, transforming into an offensive baseliner in the mid-’90s). The landscape is somewhat simplistic as players often adjusted their styles based on the surface (carpet was still popular, encouraging players to more offensive attitude indoors). The ratio of one-handed and double-handed players inside the Top 20 was pretty balanced.

In contrast, today, only two players among the Top 20 use one-handed backhands (Stefanos Tsitsipas & Grigor Dimitrov), and there’s a single style prevailing across players – offensive baselining – regardless of the surface. Among the current top twenty, only Alex de Minaur and Cameron Norrie adopt a more defensive approach during baseline exchanges. Termed “defensive baseliners,” their gameplay differs significantly from the excellent clay-courters of the mid-’90s, such as Sergi Bruguera and Thomas Muster, who operated deeper behind the baseline, with higher net clearance.

Statistical summary of these two seasons here

Born: May 24, 1987 in San Remo (Liguria)

Height: 1.78 m

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

Centre Court at a Slam, especially losing to one of the elite players in the world, presents a fitting stage to conclude a career. One month ago, this unfolded for Richard Gasquet, who stood no chance against Jannik Sinner in the second round of Roland Garros; at Wimbledon ’25, Fognini played his final match, facing Carlos Alcaraz in the first round. Fognini’s case differs slightly from Gasquet’s – the Frenchman declared beforehand that the event would mark his farewell, whereas Fognini’s decision to retire at age 38 crystallised days after a gruelling 4½-hour defeat to Alcaraz. The premier Italian born in the 1980s astonished the tennis community, pushing the two-time defending champion to the  brink despite battling injuries in recent years and losing his status as a regular ATP contender. “I think it is the best way to say goodbye,” admitted Fognini, departing the professional circuit as Italian tennis reaches unprecedented strength. “It wasn’t easy because the last three years of my career I was suffering a lot with injury. But as a competitor, I tried to do my best every time I stepped on court. Winning a Slam for me was impossible. I have to be honest. I’m happy the way I say goodbye to the professional tennis career. I did my best.”

brink despite battling injuries in recent years and losing his status as a regular ATP contender. “I think it is the best way to say goodbye,” admitted Fognini, departing the professional circuit as Italian tennis reaches unprecedented strength. “It wasn’t easy because the last three years of my career I was suffering a lot with injury. But as a competitor, I tried to do my best every time I stepped on court. Winning a Slam for me was impossible. I have to be honest. I’m happy the way I say goodbye to the professional tennis career. I did my best.”

I hadn’t considered him deeply until I witnessed his fourth-round match at Roland Garros ’11 against Albert Montañés on Suzanne Lenglen court (photo). It ranks among the most remarkable matches I’ve ever observed. The Italian fought off five match points in the decider despite being hampered by injury. I was astounded by two aspects:

– Fognini executed perfect shots with daring risk from both flanks despite limited mobility;

– knowing Montañés’ prowess, I recognised he wasn’t a player to squander match points when victory loomed.

For the Spaniard, it was also a rare chance to reach a major quarterfinal, perhaps heightening his tension; nonetheless, my impression was that Fognini clinched that “thriller” largely due to his extraordinary flair for shot-making. He had to withdraw from the quarterfinal, giving a walkover for the first time in his career.

Soon afterwards, I reviewed Fognini’s results and realized this resilience wasn’t coincidental. The player, already an ATP contender years prior, had secured qualifying victories like 17/15 (Simone Bolelli), 10/8 (Lamine Ouahab), or 11/9 (Alberto Martín) in deciding third-set tiebreaks. Indeed, in Paris a year before toppling Montañés, Fognini first drew notice with a gripping match on Philippe Chatrier court against Gaël Monfils. Fognini squandered three match points at 5:4 in the decider amid a dispute with the chair umpire, with play suspended at 9:55 p.m. The next day, the Italian survived one mini-match point at 5-all and another at 6-all to prevail 9-7 in the fifth set.

A temperamental player, occasionally displaying deplorable conduct – hurling racquets, berating those nearby – Fognini became remarkably difficult to overcome when nearing victory. I struggle to name another player born in the 1980s prone to such dramatic swings; he might have lost five games consecutively, then seize six in a row, only to drop four more. Examples of his three-set roller coasters abound. Consider these extremes: Santiago ’11, Fognini led Thomaz Bellucci 4:0 in the third set, then rallied from 4:5 (0/30) to win 1-6, 6-2, 7-6. Two years later against Monfils (again!) in Umag, he led 5:0, 5:3 (40/15) in the third, only to save two match points at 5:6 with audacious play, exiting as the victor with a 6-0, 3-6, 7-6 scoreline. That triumph over Monfils capped the finest stretch of his career, when he claimed two titles (his first at age 26, both on clay in Germany: Stuttgart and Hamburg) and amassed 13 consecutive wins before being overwhelmed in the final by Tommy Robredo. Two years earlier, their Santiago semifinal ended in a heated exchange, with Fognini labelling his rival “Hombre de mierda,” forgoing a handshake. Fognini, much like Hicham Arazi, flourished in the spotlight. When facing a theoretically superior opponent before a lively, impromptu crowd, he unleashed his finest tennis, as the burden wasn’t his to bear. Rafael Nadal knows this well – the “King of Clay” fell to Fognini four times in 18 meetings (thrice on clay!). The last defeat came when Fognini secured the pinnacle title of his career (Monte Carlo ’19). The Italian stunned the eleven-time champion in the semifinal, then overcame Dušan Lajović in an unforeseen final (having narrowly escaped elimination in the first round, trailing *1:4 to Andrey Rublev in the decider, saving five mini-match points). “I was preparing for the match as best I can because he has my ex-coach and I knew it was going to be really tough, a lot of running,” Fognini remarked after the final.

Fognini’s most memorable Grand Slam victory, showcasing his extraordinary talent, occurred at the US Open ’15, where he stunned Nadal in five sets despite losing the first two sets, achieving what seemed impossible for years – Nadal faltering after taking the opening sets. To accomplish this, Fognini played from the baseline with otherworldly precision in the latter stages of the decider, as if in a trance.

I’m uncertain how to explain why Pablo Carreño Busta was Fognini’s toughest adversary aside from David Ferrer (0-11) and Novak Đoković. Fognini lost eight times to the Serb (at the main level, once defeating him in a qualifying round at Rome ’06). Fognini required constant encouragement from his bench during an ATP Cup ’21 tie between Italy and Spain to overcome Carreño, having fallen in their initial seven encounters. Admittedly, the volatile Italian never won a set against Roger Federer (they met only four times), but among players born in the 1980s, he joins a select group with a positive record against Andy Murray – Fognini edged their rivalry 5-4, including their sole match where both were close to victory at the match’s conclusion (Shanghai ’19), an encounter marked by a heated argument between them.

Career record: 426-396 [ 394 events ]

Career titles: 9

Highest ranking: 9

Best GS result:

Roland Garros (quarterfinal 2011)

Born: July 13, 1961 in Lidköping (Västra Götaland)

Height: 1.80 m

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

Järryd’s appearances in main-level finals spanned sixteen years, with losses marking both his first (Båstad 1981) and last final (Rosmalen 1995). Above all, he was an outstanding doubles player – winning all four Grand Slam tournaments (capturing a total of eight major titles) and the Masters thrice. For over a decade, he was a cornerstone of the Swedish Davis Cup team, primarily  as a doubles specialist. Still, it’s worth highlighting that in the 1987 final against India, he was unexpectedly selected to play singles instead of the higher-ranked Stefan Edberg, and rose to the occasion. [ Järryd and his regular doubles partner for roughly three years – Edberg – had secured Sweden’s second Davis Cup victory (1984) by defeating an excellent American pair. ]

as a doubles specialist. Still, it’s worth highlighting that in the 1987 final against India, he was unexpectedly selected to play singles instead of the higher-ranked Stefan Edberg, and rose to the occasion. [ Järryd and his regular doubles partner for roughly three years – Edberg – had secured Sweden’s second Davis Cup victory (1984) by defeating an excellent American pair. ]

Two years earlier, facing India again, he and Edberg played an unforgettable opening set lasting two and a half hours, against the Amritraj brothers – winning it 21-19, before closing out the match 2-6, 6-3, 6-4. Between 1983 and 1989, Järryd participated in six out of seven successive Davis Cup finals for Sweden (excluded in 1985 – paradoxically the year when he helped his nation the most in reaching the final) – once as a singles player and five times as a doubles mainstay, partnering three different countrymen: Henrik Simonsson, Edberg, and Jan Gunnarsson.

Apart from his Swedish partnerships, Järryd also found great success with Australian John Fitzgerald, particularly in the biggest doubles events. His career draws a natural comparison to Jonas Björkman, eleven years younger. Both were more animated than average Swedish players, natural baseliners with two-handed backhands yet inclined to attacking the net, and both achieved immense success in doubles – relying more on quick reflexes than classic volleying finesse. Järryd amassed 8 singles titles and 58 doubles titles, while Björkman earned 6 in singles and 54 in doubles. Both had a deep love for representing Sweden in team competitions. Björkman, like Järryd, achieved his greatest successes thanks to his collaboration with an Australian – Todd Woodbridge (three Wimbledon titles in a row included).

Initially known as a clay-courter, Järryd’s extensive doubles schedule turned him into a dangerous floater on faster surfaces. On grass, he played his best Slam singles tournament at Wimbledon 1985; on carpet, he claimed his biggest singles title in Dallas (1986). Notably, between 1984 and 1994, he played fifteen main-level finals – all indoors (two on hard courts).

In 1993, Järryd experienced a late-career singles resurgence: as a qualifier, he stunned Boris Becker in the Australian Open first round. That victory earned him a wild card in Rotterdam, where he won the title. In just two months, he soared from world no. 151 to 77 – but it was his swan song. For the next three years, he alternated between Challengers and main-tour events.

Thanks to his longevity and exceptional doubles career, Järryd deserves recognition as the third-greatest Swede of the golden era (Joakim Nyström, Henrik Sundström & Kent Carlsson: they seemed destined for greater things than Järryd, but all of them retired prematurely) – behind only Mats Wilander and Edberg, even if his singles résumé doesn’t compare. Like Wilander and five years younger Edberg, Järryd retired in 1996 – they did it respectively in October, November, and July.

Career record: 396–261 [ 261 events ]

Career titles: 8

Highest ranking: No. 5

Best GS results:

Australian Open (quarterfinal 1987-88)

Wimbledon (semifinal 1985, quarterfinal 1987)

US Open (quarterfinal 1985)

Davis Cup champion 1984, 85 (didn’t play the final) and 87

World Team Cup champion 1988

Born: April 29, 1970 in Las Vegas (Nevada)

Height: 1.80 m

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

A prodigy, he was just 4 years old when he traded shots with the era’s top players: Ilie Năstase, Harold Solomon, and teenage Björn Borg. His father, Emanoul Aghassian (a former Armenian professional boxer who represented Iran at the Olympics in 1948 and 1952), placed tennis balls in his cradle. Aghassian – aka Mike Agassi – described his three older children as “guinea pigs” in refining the techniques he employed to shape Andre into a world-class athlete. The young Agassi captivated audiences as  the most thrilling teenager to watch in the late 1980s; at age 18 (six titles in 1988, two in the “best of five’ finals – Memphis & Forest Hills), many envisioned him as a contender for the greatest player in history. His baseline strikes from both wings were ferocious, introducing a bold innovation to the tour – no one before him played with such aggression from within the court often striking just after the bounce; incoming deep shots posed no challenge due to his superb coordination, earning him the title of the most assertive baseliner ever… admittedly he lost his first two Slam semifinals (French Open & US Open), but to the best players in the world at the time.

the most thrilling teenager to watch in the late 1980s; at age 18 (six titles in 1988, two in the “best of five’ finals – Memphis & Forest Hills), many envisioned him as a contender for the greatest player in history. His baseline strikes from both wings were ferocious, introducing a bold innovation to the tour – no one before him played with such aggression from within the court often striking just after the bounce; incoming deep shots posed no challenge due to his superb coordination, earning him the title of the most assertive baseliner ever… admittedly he lost his first two Slam semifinals (French Open & US Open), but to the best players in the world at the time.

The year 1989 marked a reversal, however; instead of claiming his first major(s), Agassi slipped in the ATP rankings (played only one big final – Rome), revealing certain flaws in his game:

– outdated landing on his right leg after the serve;

– a highly erratic game-style (low percentage of first serves in, impulsive net charges, occasional retreating on second-serve returns, expending excessive energy in the initial two hours);

– positioning himself inside the court as a receiver rendered him susceptible to failing to return more serves than his peers (however, this tactic proved a double-edged sword: Agassi maintained this stance throughout his career and was regarded as the finest returner of his era, as his counterattack became devastating whenever he accurately anticipated the serve’s trajectory);

– a front-runner mentality: he dominated many matches effortlessly, but on off days, he grew disheartened, resistant to adjusting tactics, reluctant to battle… projecting an attitude of <<I’ll win on my terms: if I can’t, I’d rather lose than win unattractively>>

I have no doubt that Agassi ranks as the second-best player of the 1990s (behind Pete Sampras) and a Top 10 Open Era player among retirees, largely due to his endurance – he’s a multiple Grand Slam champion, though reflecting on his journey, two alternate paths seem plausible:

– he could indeed have emerged as the greatest in history (at least during his era’s close);

– he might have achieved far less had he not unearthed the resolve to explore new strategies and restart

The setbacks of 1989 paled in comparison to those in 1993 (dropping to No. 31) and 1997 (plummeting to No. 141 – competing in Challengers for the first time since his teenage years, a humbling experience for someone who, just two years prior, had reigned as the world’s best!). Agassi first approached the tennis summit in late 1990 – in commanding fashion, he conquered the Masters, defeating the era’s top two players in his final two matches, then secured the opening rubber of the Davis Cup final, enabling the USA to overcome Australia by Saturday. There was little doubt that Agassi, with an enhanced serve, was destined for his inaugural Grand Slam title in the early 90s, yet it wasn’t to be – he lost in Paris (1990 and 1991) his first two finals as well as his first US Open final. The challenge was compounded by Agassi’s schedule – in his early career, he avoided trips to Australia (skipping the event in the years 1988-94!) and Britain (skipping Wimbledon in the years 1988-90). Ironically, his first major triumph came on a surface he feared after a lesson from Henri Leconte at Wimbledon ’87. In 1991, he mastery of his baseline ground-strokes, nearly reaching the semifinal (a dramatic, peculiar loss to David Wheaton). The following year, he subdued the grass-court elite in his last three matches, first overcoming Boris Becker and John McEnroe – former multiple champions of the event – then the future titlist Goran Ivanišević in a tight five-setter, despite the Croat appearing invincible with serves surpassing anyone else during the fortnight.

Two distinct years of Agassi’s career merit special recognition: 1995 and 1999. In 1995, his second coach (Brad Gilbert succeeded Nick Bollettieri) dedicated himself fully to his first of three “Andrews,” and finally, Sampras – after years of unchallenged supremacy (1993-94) – faced a worthy adversary. Their riveting rivalry of the mid-90s ignited in Paris ’94 and persisted until the US Open ’95 final, where Agassi was a slight favorite but fell in four sets, a defeat that distanced him from ending the year at the top. In 1999, triumphing at Roland Garros under extraordinarily tense circumstances throughout the tournament (i.a. he began his relationship with the best female player of the 90s – his future wife – Steffi Graf), Agassi turned into the first fully Open Era player to win all four majors (his first US Open title came in 1994, first Aussie Open a few months later)! The others to achieve a career Grand Slam were Fred Perry, Don Budge, Roy Emerson, and Rod Laver. Budge and Laver (twice) accomplished it in a single year. Laver descended to the court to present the trophy to Agassi. “To be assigned a place among some of the game’s greatest players is an honor I’ll cherish for the rest of my life,” Agassi said through tears. “I never dreamed I’d ever return here after so many years; I’m so proud. I’ll never forget this. I’m truly fortunate.” Later that year he claimed the US Open title in another five-set final which significantly helped him to finish the year as the world’s No. 1 at last.

Two phases define Agassi’s illustrious career, distinguished by his hair or its absence: 1986-94, when he sported long dyed hair, colourful outfit and chaos reigned in nearly every aspect of his on-court performance, and 1995-2006 [especially under Darren Cahill, who replaced Gilbert in 2002, becoming the oldest player ever (at the time) ranked world No. 1 in May 2003, mainly thanks to his last Slam title & capturing Miami], when he was bald, wearing a classical attire, and relentless in executing tactical plans; irrespective of this dual nature, Agassi was universally admired worldwide, though at times highly controversial (defaulted twice, arguably deserving default on several additional occasions)… Agassi is one of barely three players in history to have completed the Golden Slam, winning all four Grand Slam titles and Olympic singles gold.

Career record: 870–274 [ 320 events ]

Career titles: 60

Highest ranking: No. 1

Best GS results:

Australian Open (champion 1995, 2000-01, 2003; semifinal 1996 & 04; quarterfinal ’05)

Roland Garros (champion 1999; runner-up 1990-91; semifinal 1988 & 92; quarterfinal 1995, 2001-03)

Wimbledon (champion 1992; runner-up 1999; semifinal 1995, 00-01; quarterfinal 1991 & 93)

US Open (champion 1994, 99; runner-up 1990, 95, 02, 05; semifinal 1988-89, 96 & 03; quarterfinal 92, 01, 04)

Masters champion 1990

Davis Cup champion 1990, 92 & 95 (didn’t play in the final)

Olympic Gold medal 1996

Year-end ranking 1986-2005: 91 – 25 – 3 – 7 – 4 – 10 – 9 – 24 – 2 – 2 – 8 – 110 – 6 – 1 – 6 – 3 – 2 – 4 – 8 – 7 – 150

Born: March 22, 1975 in Zlín (Jihomoravský kraj in Czechoslovakia)

Height: 1.91 m

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

A man with flushed cheeks. I’d describe him as “a milder version of Yevgeny Kafelnikov” – both native Slavic speakers, of identical height, flat hitters, with unremarkable serves and restrained demeanour (the Russian more agitated, Novák rarely displaying emotions); shrewd baseliners disinterested in excessively prolonged rallies, occasional net assailants despite frequent doubles participation where they routinely employed serve-and-volley tactics… Kafelnikov somehow navigated a notably more triumphant career. At times, observing certain players, it’s genuinely challenging to  account for the disparity in their accomplishments.

account for the disparity in their accomplishments.

Novák managed to overcome all the premier players of his generation, except Gustavo Kuerten (never encountering either Jim Courier or Michael Chang); some of those victories were truly astonishing: 7-6, 6-3, 6-2 over Pete Sampras (Davis Cup ’00 in the United States!); two years later 7-5, 6-1 over Andre Agassi; and a commanding 6-1, 6-1 (!) over his refined counterpart – Kafelnikov in Dubai ’02! He was fortunate or skillful enough to also prevail against the young Roger Federer as many as four times (Gstaad ’03 the most important match) and emerging talents Rafael Nadal (Nadal’s Davis Cup debut, afterwards the great Spaniard won 29 consecutive matches in those competitions) and Andy Murray, once each. It’s noteworthy that Novák ranked among the most formidable early adversaries for Federer; the Swiss maestro edged their Head-to-Head just 5-4 (two wins in the finals included: Vienna ’02 and Dubai ’03), consistently faltering in their closest contests.

Novák came tantalizingly close to a big title twice in 2002:

– the first instance in the Australian Open semifinal, where he stood six points from defeating Thomas Johansson, who ultimately claimed the title… could he have bested Marat Safin in the final too? Perhaps, given their 1-1 H2H record, with Novák winning their sole Slam encounter;

– the second instance in Madrid, where he withdrew from the final against Agassi due to a leg injury he fuffered at the end of his semifinal… could he have triumphed over the renowned American? Possibly, considering he overwhelmed him weeks later in Shanghai (earlier that year they’d faced each other in Rome semifinal and the match was balanced)

Trivia:

– his first two ATP events came in Praha (years 1993-94), falling twice to Sergi Bruguera, who arrived in the Czech capital as a Roland Garros champion on both occasions.

– within half a year, he toppled Carlos Moyá twice, saving match points each time – first in the aforementioned Madrid (indoors), then at the World Team Cup (outdoors). He secured 13 of his 18 doubles titles alongside David Rikl (born 1971), Kafelnikov’s initial doubles partner, incidentally.

Career record: 337-260 [ 259 events ]

Career titles: 7

Highest ranking: No. 5

Best GS results:

Australian Open (semifinal 2002)

Born: June 18, 1986 in Béziers (Occitanie)

Height: 1.83 m

Plays: Right-handed

Great anticipation surrounded Gasquet in France when he debuted at an ATP event – Monte Carlo ’02 before turning 16. In the opening round, as a qualifier [589], he astounded spectators by overcoming former French Open semifinalist Franco Squillari, becoming one of the youngest match victors at the main level of the Open Era. This milestone preceded his first  Challenger event, which he subsequently conquered (Montauban) not dropping a set; a month earlier at the French Open, he’d seized the opening set from Albert Costa, who claimed the trophy two weeks later! No one questioned that the young prodigy possessed remarkable talent to be hypothetically remembered as one of the best players of the first decade of the new century.

Challenger event, which he subsequently conquered (Montauban) not dropping a set; a month earlier at the French Open, he’d seized the opening set from Albert Costa, who claimed the trophy two weeks later! No one questioned that the young prodigy possessed remarkable talent to be hypothetically remembered as one of the best players of the first decade of the new century.

For the following two years, Gasquet was frequently compared to his contemporary, two weeks older Rafael Nadal. They finally clashed in a captivating semifinal in Monte Carlo ’05 (after Gasquet had outlasted Roger Federer a round earlier, surviving three match points). Afterwards, their once-parallel paths diverged starkly (18-0 for Nadal in the end, the second most one-sided Head-to-Head in modern times) – the Spaniard emerged as the ‘King of Clay,’ an undisputed No. 2 in the world for several years behind Federer, while Gasquet never breached the Top 5, soon recognizing that two players a year his junior (Novak Đoković and Andy Murray) were destined for greater heights. Not only the Monte Carlo semifinal, but also the Estoril ’07 final and Wimbledon ’08 fourth round, proved revealing – Gasquet displayed flashes of brilliance, yet lacked the endurance and resolve of his peers. That fourth-round encounter at Wimbledon ’08 would linger in Gasquet’s memory for the rest of his career; having bested Murray in their two prior meetings, he fell to the Scot despite nearing victory in three relatively straightforward sets. That defeat was no anomaly; it underscored Gasquet’s delicate psyche.

His exquisite backhand (arguably the best one-handed BH in the 21st Century thus far) could captivate audiences in the grandest arenas, but tennis demands resilience in countless critical moments – a quality Gasquet sorely lacked. This inability to summon something extraordinary led to even more devastating two-set-to-love (MP-up) losses at the Australian Open in consecutive years (to Fernando González 10-12 in the 5th after four hours and Mikhail Youzhny after ~five hours – second time to him after such a long match). Therefore I believe those setbacks shaped Gasquet’s trajectory, even though he was merely 24 years old. It was clear he wouldn’t be a one Slam wonder.

The year 2013 marked the peak of Gasquet’s career – he secured three titles (Doha, Montpellier, Moscow) and reached the US Open semifinal, overcoming a lingering five-set jinx by defeating Milos Raonic and David Ferrer in consecutive five-set battles; the latter victory was particularly noteworthy, as Gasquet snapped a streak of five straight losses to the Spaniard without winning a set. Another celebrated five-set triumph came at Wimbledon ’07, where he toppled Andy Roddick in a rare scenario among five-setters, clinching the final three sets despite nearly losing each. That win propelled him to his first major semifinal; his third and final one also occurred at Wimbledon (2015), where he once again defied expectations by outlasting Stan Wawrinka in a thrilling showdown.

Gasquet’s very long career – likewise Gaël Monfils‘ – despite high hopes of the potent French federation, registers as a considerable let-down, though he enjoyed one of the most enduring careers, as evidenced by the number of tournaments he contested (only three men have played more main-level events than him). He reached 33 finals, three at the Masters 1000 level (Hamburg ’05, Toronto ’06, and Toronto ’12). Given twenty consecutive years in the Top 100, three Slam semifinals as well as three big finals, it’s a blow for Gasquet’s legacy he never won an ATP 500 title, also the fact he never played a semifinal at the French Open (only one quarterfinal, in 2016). Undoubtedly, his failure to ever defeat Nadal casts a shadow over his glorious tennis adventure, but he departed the court victorious against Đoković on one occasion in fourteen meetings, and several times when Federer (2-19 in their H2H) and Murray (4-9 H2H) stood across the net: Rome ’12 remains the most cherished memory because the fragile Gasquet was physically stronger than the Scot at least on that day.

Career record: 610-408 [ 420 events ]

Career titles: 16

Highest ranking: No. 7

Best GS results:

Roland Garros (quarterfinal 2016)

Wimbledon (semifinal 2007 & 2015)

US Open (semifinal 2013; quarterfinal 2015)

Davis Cup ’17 champion (played doubles in the final)

Hopman Cup ’17 champion

Born: August 16, 1964 in Grand Island (New York)

Height: 1.74 m

Plays: Right-handed

Alongside Aaron Krickstein (their match in Antwerp ’86), Arias was expected to succeed Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe at the zenith of U.S. tennis in the second half of the 1980s. They were both the inaugural “products” of Nick Bollettieri’s renowned academy, prodigies, hypothetical US versions of Björn Borg. Arias was merely 16 years and 10 months old when he claimed his first significant title – the mixed-doubles crown at the French Open ’81, partnering his  female counterpart Andrea Jaeger; a few months earlier, he’d become the youngest player (at the time) to compete in the US Open, losing in straight sets to Roscoe Tanner in the second round.

female counterpart Andrea Jaeger; a few months earlier, he’d become the youngest player (at the time) to compete in the US Open, losing in straight sets to Roscoe Tanner in the second round.

He entered the Top 100 before turning 17, and the pinnacle of his career unfolded around age 20 – he shockingly triumphed in Rome ’83, then proved his mettle in prestigious tournaments where was stopped in later stages by the era’s top three players (US Open, Dallas, French Open), and a soon-to-be top player Stefan Edberg in the first Open Era Olympic Games – as a demonstration sport for the second time in sixty years (only 21 year-old or younger men could participate). He ascended to the Top 5 as a teenager, yet those three hyperlinked lost matches to the game’s giants exposed his limitations; while it was improbable he’d become the world’s best, few anticipated his descent into mediocrity in the latter 1980s (his sole notable result being the Monte Carlo ’87 final).

Arias exemplified rapid exploitation. He had secured five titles before turning twenty and added none to his résumé thereafter (losing seven finals in the years 1985-1991). Still relatively young at 30 years old, he retired following several lackluster years and persistent injuries. Unexpectedly, he re-emerged for his cameo ATP event four years later – navigating the qualifying rounds in Washington ’98 (defeating Doug Flach and Eric Taino) to capitalize on a favorable draw, and Wade McGuire’s (poor 7-20 main-level record) injury in the first round… though he stood no chance against Wayne Ferreira in the second round.

Arias reflects on his career: “At 19, I made one critical mistake that altered my career. I contracted mono and continued playing, which enlarged my spleen and triggered liver issues. I was prescribed three months of bed rest. I began reviewing all the scrapbooks my mother had compiled, and I had two troubling thoughts: the first was, ‘if I never accomplish anything else in tennis, I’ve already done well.’ What you say manifests. I never truly achieved anything else I deemed noteworthy, though I won some significant matches. The second thought was even more unsettling: ‘I didn’t want to be No. 1 in the world anymore.’ The fame was too intense for my liking. I wanted to enjoy a movie without everyone recognizing me.” Yet the truth is that under Bollettieri’s guidance, Arias honed a potent top-spin forehand with a wooden racquet; it was a period of transition to graphite, and from the mid-1980s onward, several moderate players adeptly countered Arias’ top-spins once equipped with modern gear. Moreover, Arias’ backhand lacked fluidity; being short in stature, once his primary weapon was neutralized, he had no other arsenal to challenge the best guys on the tour.

Trivia: Arias was implicated in arguably the most humiliating defeat of the U.S. Davis Cup team in the 1980s. In the 1987 first round, Americans travelled to Paraguay as overwhelming favorites; Arias lost two rubbers, the second pivotal one against the obscure Hugo Chapacu [ranked 282] after 5 hours and 22 minutes, squandering three match points, the first two while leading 5:1 (40/15) in the decider! Another striking Arias defeat in the 1980s occurred at Barcelona ’84, where he fell in the quarterfinals to Sweden’s Joakim Nyström 6-2, 4-6, 14-16 – Arias trailed 1:5 in the third set yet held a match point at 12:11. That unfortunate loss actually meant Arias’ departure from the tennis elite.

Career record: 283–222 [ 222 events ]

Career titles: 5

Highest ranking: No. 5

Best GS results:

Roland Garros (quarterfinal 1984)

US Open (semifinal 1983)

World Team Cup champion 1984

Bronze medallist of the Olympics (Los Angeles ’84)

Born: September 15, 1971 in Johannesburg (Gauteng)

Height: 1.83 m

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

Along with Richard Krajicek, (and Carlos Costa, MaliVai Washington to a lesser extent), Ferreira was the most significant revelation of the 1992 season. They were both 20-year-olds when they reached the Australian Open ’92 semifinals. Krajicek delighted the tennis world with a booming serve and exceptional volleying skills, while Ferreira showcased a lethal forehand. Ferreira’s career proved lengthy and rewarding; in a sense, he became an emblem of Grand  Slam events, never missing a major between the Australian Open ’91 and US Open ’04 (as many as 56 consecutive Grand Slams – a record at the time), when he recognized it would be his not only final tournament at that level, but also his last main-level event altogether (332nd in total).

Slam events, never missing a major between the Australian Open ’91 and US Open ’04 (as many as 56 consecutive Grand Slams – a record at the time), when he recognized it would be his not only final tournament at that level, but also his last main-level event altogether (332nd in total).

Despite such numerous appearances at majors, and a commendable five-set record, he never experienced a year as successful at Slams as in 1992, when he followed up the Aussie semifinal with a US Open quarterfinal and a fourth-round showing at Wimbledon (in all those events, he was ultimately defeated by exceptional players on Centre Courts). To me, he is regarded as the finest Open Era player never to reach a major final. He came nowhere close; in 1992 as well as in 2003, he had little chance in Melbourne, facing Stefan Edberg and Andre Agassi respectively in the semifinals. Agassi was indeed Ferreira’s nightmarish adversary. They met eleven times, and only once did Ferreira come close to victory, in their match no. 6 – at the Olympic Games in Atlanta ’96. The South African led 5:3* (30-all) in the decider when netted Agassi’s conservative second serve before succumbing 5-7, 6-4, 5-7. Against the other premier player of the 90s – Pete Sampras – Ferreira performed admirably. He lost their Head-to-Head 6-7, but from 1995 to 1998, Ferreira triumphed in all four encounters (always 6-3 in the third sets), and what’s notably amusing, the first two wins (Lyon and Frankfurt) followed the same pattern as the subsequent two (Key Biscayne and Basel). Apart from Agassi & Michael Chang, Ferreira vanquished all players who epitomized the decade; as a veteran, he remained a formidable opponent for emerging talents (two highly dramatic victories over Lleyton Hewitt – in five meetings, also two against Roger Federer – in three meetings).

Ferreira was an offensive baseliner, yet playing at the net felt like his natural domain (he regularly participated in doubles competitions; the best junior in doubles of 1989, got the Olympic silver medal in 1992 alongside Piet Norval). Serve-and-volley tactics were second nature to him on grass, while on hard courts and indoors, he employed this style according to necessity. I believe his inability to defeat Agassi at least once may be attributed to this – he couldn’t rival Agassi from the baseline, but his serve-and-volley skills proved insufficient to overcome the great American with a plan B; he could only hope for a subpar day from his nemesis, which occurred in Atlanta… Who knows, perhaps if he had defeated Agassi then, he might have claimed a gold medal, offering him some measure of fulfillment.

I assume that two Mercedes Super 9 titles (Toronto ’96 and Stuttgart ’00) provide some compensation for not securing anything grander. If we compare Yevgeny Kafelnikov and his frequent doubles partner Ferreira (5-3 in their matches for the Afrikaner), both versatile players adept at winning matches in the 90s by attacking the net and playing from the baseline depending on the surface and the opponent, there’s actually no disparity between them in technical-mental skillset. Yet the Russian captured two majors and an Olympic gold medal. Suggesting that the Russian capitalized on clay-courts as a European would be an oversimplification, as Ferreira advanced to the Stuttgart-outdoor ’92 final when the event boasted its strongest field in history, and two Rome semifinals (1995 & 1996) when the Italian capital held the status of the second most prestigious clay-court event behind the French Open.

“I had on occasions felt that I lost to players who I should have beaten, and this is something I became aware of much later in my career. Often I would take the first set easily and then I became bored. I would lose interest and then sometimes didn’t recover sufficiently to win the match,” Ferreira reflected on his career. Trivia: Ferreira was the hottest player around the US Open 1994: he won four titles (three in consecutive starts) – first he captured Indianapolis – his lone title being an equivalent of ATP 500; the following year, he claimed back-to-back European events indoors in autumn, then reached the semifinal at Paris-Bercy. In hindsight, it seems the US Open ’94 was the Slam when Ferreira was in peak form to reach his sole major final; unfortunately for him, in the third round, he faced his toughest opponent, Agassi, and lost in straight sets – it was Ferreira’s only defeat within 25 tournament matches!

Ferreira returned to the circuit after fifteen years as Frances Tiafoe’s coach. They collaborated from 2020-23, with Ferreira guiding him to a Top 10 ranking. Recently, Ferreira has been mentoring a player aiming to break into the Top 20 – Alexei Popyrin.

Career record: 512–330 [ 332 events ]

Career titles: 15

Highest ranking: No. 6

Best GS results:

Australian Open (semifinal 1992 & 2003; quarterfinal 2002)

Wimbledon (quarterfinal 1994)

US Open (quarterfinal 1992)

Hopman Cup 2000 champion

Born: October 2, 1967 in Leibnitz (Styria)

Height: 1.81 m

Plays: Left-handed

Speaking percentage-wise, Muster’s finest Slam was Roland Garros (71% of wins), yet he played as many quarterfinals at the Australian and US Opens as in Paris, which is rather unexpected. It becomes less surprising upon closer examination of Muster’s decade in Paris, starting in 1989, when he had reached an Australian Open semifinal and advanced to the Key Biscayne final (Ivan Lendl proved an insurmountable barrier both times), becoming a recognisable force in tennis. That year, he was sidelined for six months by a car accident (struck by a drunk driver; side ligaments in his left knee torn).

In 1991, he fell in the first round to the decade’s finest player – Pete Sampras. The years 1992 and 1993? Twice thwarted by the reigning champion in Paris at the time – Jim Courier. In 1994 – another challenging draw, a gruelling second-round victory over Andre Agassi, followed by a stunning defeat to Patrick Rafter, who’d later rise to become the world’s best, lending that match a different perspective with hindsight. In 1996? A fourth-round exit when Muster was expected to defend his title, but he was ousted by an inspired Michael Stich. That year, the sunny conditions favored big servers, and Stich capitalized on the weather. In 1997? A shocking loss, then not in a hindsight – third-round defeat to Gustavo Kuerten, who went on to win the event and secure two more titles in Paris. Finally, in 1999, a first-round defeat marked the end of his career, falling to Nicolás Lapentti, who was playing the tennis of his life that year. Thus, we see only three advancements to the quarterfinals: first in 1990, when Muster fell in the semifinal to Andrés Gómez after defeating the Ecuadorian weeks earlier in the Rome semifinal; the title in 1995, when Muster, an overwhelming favorite, narrowly escaped in the last eight (against Albert Costa); and the quarterfinal in 1998 (defeated by Félix Mantilla – top clay-courter in the second half of the 90s), by which time the greatest Austrian of the Open Era was already vulnerable to upsets on clay, and few would have been shocked if he had exited in the first week.

In 1991, he fell in the first round to the decade’s finest player – Pete Sampras. The years 1992 and 1993? Twice thwarted by the reigning champion in Paris at the time – Jim Courier. In 1994 – another challenging draw, a gruelling second-round victory over Andre Agassi, followed by a stunning defeat to Patrick Rafter, who’d later rise to become the world’s best, lending that match a different perspective with hindsight. In 1996? A fourth-round exit when Muster was expected to defend his title, but he was ousted by an inspired Michael Stich. That year, the sunny conditions favored big servers, and Stich capitalized on the weather. In 1997? A shocking loss, then not in a hindsight – third-round defeat to Gustavo Kuerten, who went on to win the event and secure two more titles in Paris. Finally, in 1999, a first-round defeat marked the end of his career, falling to Nicolás Lapentti, who was playing the tennis of his life that year. Thus, we see only three advancements to the quarterfinals: first in 1990, when Muster fell in the semifinal to Andrés Gómez after defeating the Ecuadorian weeks earlier in the Rome semifinal; the title in 1995, when Muster, an overwhelming favorite, narrowly escaped in the last eight (against Albert Costa); and the quarterfinal in 1998 (defeated by Félix Mantilla – top clay-courter in the second half of the 90s), by which time the greatest Austrian of the Open Era was already vulnerable to upsets on clay, and few would have been shocked if he had exited in the first week.

“Muster reminds me a lot of Guillermo Vilas because he hits the ball so hard,” Gómez remarked after the upset loss in Rome ’90. This echoed my own impression watching Muster in the 90s; he played in a manner that suggested he modelled his game-style on the Argentine icon of the 70s. Exceptional athleticism, abundant topspin off both wings generated with the left hand, and a deft touch at the net (when Muster was developing, he played doubles frequently, like many Europeans) – these traits they shared. Muster was a relentless worker, a necessity to regain his former level after the Key Biscayne accident. He was famously photographed hitting tennis balls from a specially designed chair, his left leg in a cast. Six months later, he returned and was named the ATP’s Comeback Player of the Year. The immense effort he invested in reclaiming his peak form yielded rewards in 1995 – that year, Muster was utterly dominant on his cherished clay, securing twelve titles (three Masters 1K; Monte Carlo, Rome, Essen) in fourteen finals (paradoxically lost two in front of the home crowd: Kitzbühel and Wien), eleven on the dirt. It’s truly remarkable that en route to half of titles, he was one point from defeat (winning seven match-point-down matches in total that year)!

His dedication to amassing as many titles as possible paved the way for him to become world No. 1, which he achieved the following year, despite not playing with the same efficiency on clay, though he improved on faster surfaces, even managing to win some matches on his despised grass (his Wimbledon record? A dismal 0-4; from 1988 to ’91, he didn’t even bother travelling to England). “My No. 1 ranking in 1996 was built on my 12 tournament wins in 1995… I don’t know how many people can say that, measurably, they have been No. 1 at something, the best in the world. I loved that moment,” Muster reflected, explaining that he spent six weeks on the top at the time of his sensational defeats on hardcourts in the first quarter of 1996.

He aimed to prove to the era’s top players (Agassi and Sampras) that he could compete with them on all surfaces. Starting from Queens Club 1996, Muster quickened his first serve, began operating closer to the baseline, attacking the net more frequently (as he had in the late 80s), and 1997 marked his strongest year on hard courts (Australian Open semifinal, Dubai & Key Biscayne triumphs, final in Cincinnati). However, he lost his mastery on clay with this new implementation, winning just 9 matches (and losing 9) on that surface that year, a stark contrast to his stellar 65-2 (1995) and 46-3 (1996) records in the prior two years. When young Àlex Corretja stunned him 7-5, 6-1 in the Gstaad ’95 first round, it ended Muster’s 35-match winning streak (40 on clay).

While analyzing Muster’s matches, I’ve observed he was inclined to use lobs despite not executing them effectively; his return was mediocre, often merely blocking on the backhand side. This may explain his lackluster Head-to-Head records against serve-and-volleyers; he possessed only average reflexes and often, instead of attempting passing shots, resorted to defensive lobs. An embarrassing 0-10 H2H against Stefan Edberg is striking, but he also struggled against other similar players: 0-3 vs. Rafter, 2-3 vs. Stich. Moreover, he had even records against serve-and-volley big servers like Goran Ivanišević and Richard Krajicek, all of whom could defeat Muster even on clay.

Muster accomplished an infamous feat previously seen only in Björn Borg’s case, returning to the tour a decade after his final professional match. Across all levels, he competed in 26 matches during 2010-11, securing just two victories, one particularly gratifying (Todi, Challenger) – Muster overcame Leonardo Mayer, a player twenty years his junior, who would later rise to No. 21.

Career record: 625–273 [ 308 events ]

Career titles: 44

Highest ranking: No. 1

Best GS results:

Australian Open (semifinal 1989 & 97; quarterfinal 1994)

Roland Garros (champion 1995; semifinal 1990; quarterfinal 1998)

US Open (quarterfinal 1993-94 & 96)

Year-end rankings 1984-99: 311 – 98 – 47 – 56 – 16 – 21 – 7 – 35 – 18 – 9 – 16 – 3 – 5 – 9 – 25 – 193

Born: June 28, 1973 in Bilbao (País Vasco)

Height: 1.72 m

Plays: Right-handed

…if Jean Borotra (1898–1994), one of the famed French ‘Four Musketeers’ of the interwar period, stands as the greatest Basque player in history, Berasategui at least deserves the title of ‘best Basque player’ of the Open Era.

The 1994 it was his year to some degree (merely Pete Sampras won more titles that year; btw Sampras is the only top player born in the 70s, Berasategui never faced), he brought back something that had been seen in 1988 when Kent Carlsson advanced to the Top 10 while focusing only on clay. Both Berasategui and Carlsson played with enormous topspin forehands, but in Berasategui’s case, there was something unseen before: he hit the ball aggressively off both  wings with the same grip!

wings with the same grip!

Nothing strange about that for players of many previous generations, who grew up with wooden racquets and adjusted to the continental grip. But to play this way with modern graphite equipment – hitting every shot with the same side of the racquet – it was a bizarrely tough task. Berasategui somehow found a way; with such an extreme forehand grip, and exceptionally fast pace between points on serve, his topspin was really impressive. In the mid-90s, heavy topspin wasn’t as popular as it would become in the next decade. The Basque took full advantage of it on clay, moving smoothly with his wiggly legs to produce forehand winners all over the place.

First he gained some attention in the fall of 1993 by reaching four small ATP finals (lost three of them, always in deciders). He sent a serious message to the top players in Nice ’94, defeating Jim Courier 6-4, 6-2 in the final – Courier, at the time, had played three consecutive French Open finals. Berasategui’s great form in southern France carried over to Paris: at Roland Garros ’94, he was brilliant for two weeks. Before that event, he’d never even reached a Slam third round, yet suddenly he was in the final, eliminating only quality opponents: Wayne Ferreira, Cédric Pioline, Yevgeny Kafelnikov, Javier Frana (b. 1966, three titles), Goran Ivanišević, and Magnus Larsson. Even though none of his opponents (five of six potential Top 10 players, excluding Frana) were typical clay-courters, the fact that Berasategui didn’t drop a set was really astonishing.

In the final, he faced a Davis Cup mate and defending champion – Sergi Bruguera. In the first all-Spanish major final, witnessed by the Spanish king Juan Carlos I, the Basque was defeated in four sets by the Catalan, who neutralized Berasategui’s kick-serve and simply outlasted him. The Parisian fortnight boosted Berasategui’s confidence – afterwards, he won six titles in the second half of the season (seven including a Challenger), the biggest in Stuttgart. He went unbeaten on clay for 27 straight matches (22 excluding a Challenger title in Barcelona), earning a spot at the Masters. There, he became a whipping boy; unlike Carlsson in 1988, Berasategui switched from clay to carpet, where Michael Chang, Andre Agassi, and Bruguera destroyed him. The latter felt so confident that I saw him serve-and-volleying regularly for the first time.

Berasategui was never the same after 1994. Opponents figured him out – his tendency to serve almost exclusively to right-handed backhands on the deuce court (standing unusually close to the center mark – in the mid 90s only Gilbert Schaller had higher % of first serves in) and his habit of running around his backhand for those vicious topspin forehands. Covering ~75% of the baseline with the forehand is never easy – it requires endless running and power – it’s even harder for a player of his modest stature. Once his fitness dipped, his exposed backhand became prone to errors.

Strangely, his second-best major performance came on hard courts – the 1998 Australian Open, where he reached the quarterfinals beating Andrei Medvedev, Patrick Rafter, and Agassi as an underdog, in succession. Yet between June 2nd and August 31st that year, he lost nine straight main-level matches! Before that skid, he suffered two brutal collapses: leading 5:1 in the deciders against Pioline (Monte Carlo) and Félix Mantilla (Hamburg); he wasted eleven match points combined. Berasategui retired at age of 27, with a 14-9 record in ATP finals – all on clay (Carlsson, with a distinctively shorter career, finished at 9-8). He played one semifinal outside clay (Scottsdale ’96), Carlsson did not.

Career record: 278–199 [ 207 events ]

Career titles: 14

Highest ranking: No. 7

Best GS results:

Australian Open (quarterfinal 1998)

Roland Garros (runner-up 1994)

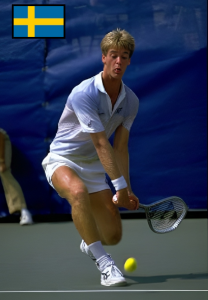

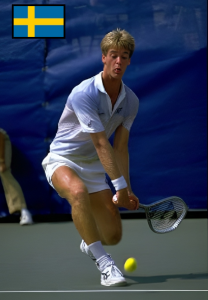

Born: March 23, 1972 in Alvesta (Kronoberg)

Height: 1.84 m

Plays: Right-handed (two-handed backhand)

Björkman was an heir to two different schools of Swedish tennis: one represented by a bunch of players inspired by Björn Borg, who used two-handed backhands and built their tactics around ground-strokes, and the other represented primarily by Stefan Edberg, the serve-and-volley style. Björkman tried to combine these two schools (similarly to Anders Järryd in the preceding decade), even though his volley skills were nowhere close to Edberg’s, and his forehand lacked the power of the three Magnuses (Larsson, Norman, and Gustafsson), who played more or less at the same time. He had to invent this hybrid supported by exceptional physical preparation because as a junior glued to the baseline he sunk in European mediocrity.

Björkman first showed signs of his potential at the US Open 1994, where he destroyed his idol Edberg in the third round before advancing to the quarterfinals. A few months later he reached the Key Biscayne ’95 semifinals after eliminating Mats Wilander, arguably the second-best Swede born in the 60s.

Björkman first showed signs of his potential at the US Open 1994, where he destroyed his idol Edberg in the third round before advancing to the quarterfinals. A few months later he reached the Key Biscayne ’95 semifinals after eliminating Mats Wilander, arguably the second-best Swede born in the 60s.

In those early years on ATP tour (mid-90s), he established himself as one of the best doubles players, partnering fellow Swede Jan Apell, who is three years older. The constant net attacks behind each serve in doubles and improved return skills (in the 90s only Paul Haarhuis could deal with service bombs as good as Björkman), he successfully transferred into his singles career by 1997. At 25, as a serve-and-volley player relying on his satisfactory first serve, attacking the net a lot with approach-shots as a receiver, he enjoyed a memorable season from start to finish (he moved from No. 69 to 4 that year): began it with a title in Auckland, finished with a Davis Cup triumph (leading Sweden in both singles and doubles alongside Nicklas Kulti), in the meantime he captured his biggest career title – Indianapolis (an equivalent of today’s ATP 500). He also reached his first Grand Slam semifinal at the US Open, highlighted by another stunning third-round victory over the reigning French Open champion.

The last quarter of that season was particularly impressive: including the US Open, Björkman won 25 of 32 matches, reaching at least the semifinals in four consecutive indoor events (Paris-Bercy marked his first and last Masters 1K final). The crowning achievement was his four-set victory over Michael Chang in the opening rubber of the Davis Cup final, setting the tone for Sweden’s 5-0 humiliation of the Americans.

The magic faded after the 1998 Australian Open (the only Slam where Björkman was considered a title favorite). He lost in the quarterfinals to veteran Petr Korda despite winning the first two sets, and his terrific form soon evaporated (between the Dubai semifinal and the grass-court ’98 season, he won only 4 matches losing 11). Still, for another ten years of his career, he remained a permanent Top 100 player, capable of occasional surprises at big tournaments (like his Wimbledon ’06 semifinal run at 34), leveraging his vast experience in best-of-five matches. Due to his longevity he played for the entire 90s (1-9 record against the decade’s best Pete Sampras) and almost the entire 00s (0-5 against the decade’s best Roger Federer). The only other player who experienced something similar is Fabrice Santoro, the Frenchman’s career stretched even longer, between 1989 and 2010.

In the 90s, Björkman was the only player – alongside Guy Forget – to compete in the “Masters” events in both singles (1997 semifinalist) and doubles (1994 champion). Off the court, he was known for his amusing player impersonations (John McEnroe, Emilio Sánchez, Edberg), which Eurosport often featured. Post-retirement, he teamed up with fellow Swedish pros Thomas Johansson and Simon Aspelin to create a club league for amateur players. In 2015 he was coaching Andy Murray, but didn’t help him to reach the top spot.

Career record: 414-362 [ 349 events ]

Career titles: 6

Highest ranking: No. 4

Best GS results:

Australian Open (quarterfinal 1998 and 02)

Wimbledon (semifinal 2006; quarterfinal 2003)

US Open (semifinal 1997; quarterfinal 1994 and 98)

Davis Cup champion 1994, 1997 & 1998 (twice in doubles, once in singles/doubles)

World Team Cup champion 1995